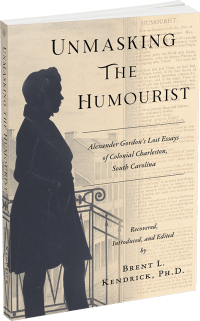

This week’s post is arriving early, because in just a few days I will step into a room filled with history and voices that refuse to fade. On October 1, the Charleston Library Society—the oldest cultural institution in the South and the second-oldest circulating library in the nation—will host the launch of my Unmasking The Humourist: Alexander Gordon’s Lost Essays of Colonial Charleston, South Carolina.

Why Charleston? Because the city itself is part of the story. It was here, in November 1753, that Alexander Gordon began publishing his Humourist essays in The South-Carolina Gazette. Through wit and irony, Gordon held up a mirror to colonial society, skewering hypocrisy, praising learning, and questioning authority. His essays pulsed with the contradictions of a city that was both refined and raw, elegant and quarrelsome. Charleston was his stage, and for nearly three centuries his voice remained hidden in the fragile pages of a newspaper few had cause to revisit.

That is, until now.

The Charleston Library Society is not just the venue for this launch—it is the very repository that safeguarded the Gazette itself, preserving the faint ink on brittle pages that carried Gordon’s words into the future. Founded in 1748, just five years before The Humourist first appeared, the Library has weathered fires, wars, earthquakes, and centuries of change. Its shelves and archives testify to the endurance of ideas—and to the truth that words matter. To stand in this place and reintroduce Gordon’s voice is both an author’s honor and a literary historian’s homecoming.

This launch also falls on a milestone: 272 years since the first Humourist essay appeared in Charleston. That span of time is almost unimaginable. Empires have risen and fallen, nations have been born, wars have been fought, and yet these essays—sharp, funny, insightful—still breathe. They remind us that human folly, ambition, vanity, and hope are constants. Gordon was not writing only for 1753. He was writing for us.

For me, this book represents years of research and a kind of detective work: following a trail of clues, comparing voices, weighing evidence, and finally piecing together the case for Gordon’s authorship. It is scholarship, yes—but it is also a story of recovery. Of bringing back a writer who deserved to be remembered, who deserves a place in our understanding of American letters.

And so, on October 1, Unmasking The Humourist will take its first public bow in the very city that first gave it life.

If you are in or near Charleston, I would be delighted to see you at the Charleston Library Society. If you are far away, I hope you will celebrate with me from wherever you are.

Because this launch is not just mine—it belongs to every reader who believes in the power of words to survive, to provoke, to amuse, and to endure.

About the Book

This edition definitively establishes Alexander Gordon (c. 1692–1754)—antiquarian, Egyptologist, scholar, singer, and later Clerk of His Majesty’s Council of South Carolina—as the author of The Humourist essays, restoring his rightful place in literary history.

The Introduction confirms Gordon’s authorship and provides the necessary historical context surrounding the essays and their publication in The South-Carolina Gazette.

The Humourist Essays section presents the complete authoritative text. Each essay is introduced with a detailed headnote offering historical context, exploring key themes, and situating the essay within broader literary and cultural traditions. These headnotes also clarify references, highlight rhetorical and satirical techniques, and connect The Humourist to its periodical essay tradition. Following each essay, explanatory notes supply annotations that illuminate historical allusions, linguistic nuances, and biographical details, making the essays more accessible to modern readers while preserving their original wit and bite.

The Afterword suggests areas for future scholarship—richer literary analysis of Gordon’s techniques, his engagement with Charleston’s intellectual and political life, his later years in South Carolina, and his place in transatlantic literary traditions. This volume thus serves both as a definitive authorship study and as a definitive text, laying a foundation for future research.

Finally, the Appendix corrects a 277-year-old historical error that mistakenly attributed to Gordon a natural history of South Carolina. This archival correction not only restores the record but also underscores the importance of rigorous scholarship—whether in reclaiming a forgotten author’s voice or in ensuring that legacy is preserved with accuracy.

Unmasking The Humourist: Alexander Gordon’s Lost Essays of Colonial Charleston, South Carolina is available now:

Amazon and Barnes & Noble

All proceeds from the sale of this book will be donated to The Virginia Foundation for Community College Education