“Life is a becoming, not a being.”

—Carl Jung (1875-1961). Swiss psychiatrist and founder of analytical psychology.

My dream life has always been rich, layered, tapestried, and almost theatrical in its staging. I rarely dream about daily life. My dreams take place in cities I’ve never visited, landscapes that I’ve never seen, and eras long before or long after my own. And yet I always feel at home in them.

Usually, everything arrives in extravagant, saturated Technicolor.

But not this one.

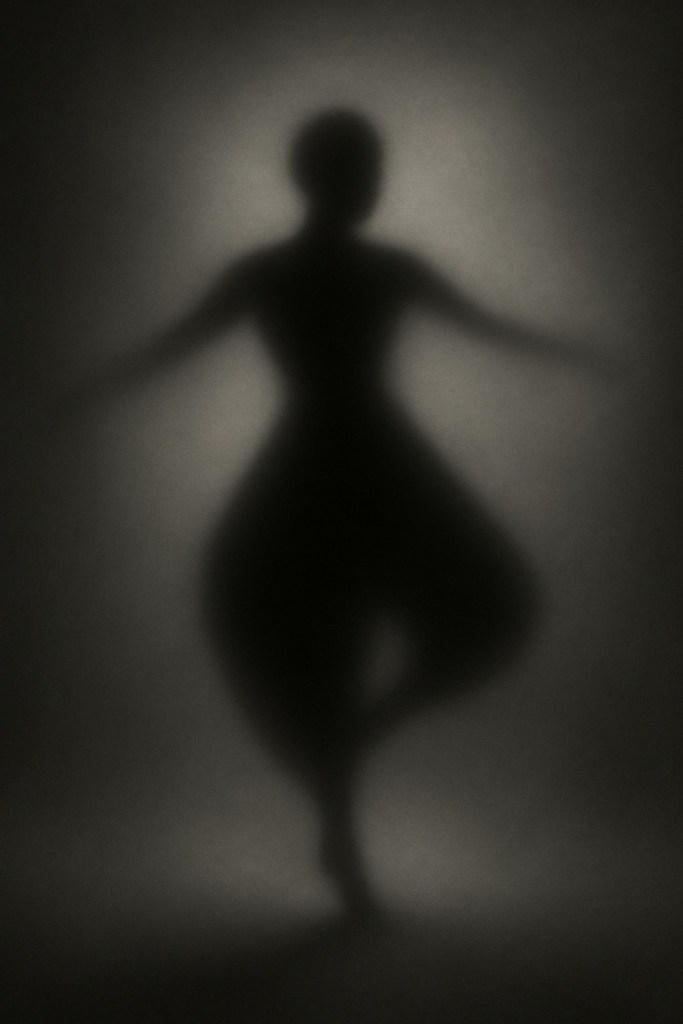

Two nights after my seventy-eighth birthday, in the soft slumber between 6:06 and 6:30 a.m., I slipped into a dream unlike any I’ve ever had. It came in intense gradients of black, white, and gray. It was as if my subconscious had switched from paint to charcoal. When I woke, the dream woke with me, fully intact, waiting patiently for me to reflect.

I stood in an indoor space. It was a hall, a room, or perhaps a gathering place, and I was part of a crowd. I couldn’t tell you who the people were. Their faces were blurred, unreal, more like presences than individuals. Witnesses. Shapes. A chorus.

And then—

I saw them.

At first, they appeared as an elderly Black woman who was petite but arresting in presence. Their deeply ebony skin was creased and chiseled, textured like something carved rather than aged. Their hair fell in short, curved bangs and soft, tucked-under curls. Their eyes were dark, bottomless, and profoundly alive. They seemed not so much eyes as portals.

Then they began to twirl.

Slowly. Fluidly. Without strain or wobble. They descended toward the floor as if melting into themselves, spinning in a movement so smooth it seemed beyond anatomy. No catching of balance, no hesitation. It was just a gentle spiraling downward until they were nearly seated on the ground. Then, just as seamlessly, they spiraled upward again, rising on a single leg with the poise of something birdlike. Ancient. Balanced. Perched.

And in that rising, the transformation began.

Their skin tautened, and their features sharpened. The nose took on a beak-like elegance. The cheekbones drew higher. The eyes moved deeper into shadowed hollows. Their face tightened into something more elemental than human. They executed a slow, miraculous somersault. While still balanced on a single leg, they landed perfectly, continuing the twirl without effort, without breathlessness, without age.

By the time they came to stillness, they were statuesque, unshakable, and alive. Their gender had fallen away. What had begun as an old woman had become something older, an archetype, a presence, a force.

Through all of it, they moved with an ease that felt destined. No strain. No doubt. No pause to gather balance. The certainty with which they descended, ascended, transformed, and landed was astonishing. It was more than grace. It was alignment. It was a being doing exactly what they were meant to be doing, as naturally as breathing.

I felt awe. I felt love. A quiet message rose inside me:

Look at what is possible.

Look at what we can become.

I call them Ebony.

Dreams this vivid don’t arrive as entertainment. They arrive as instruction. And this one, with its charcoal palette and its slow, impossible choreography, came carrying meaning that was mythic, psychological, and deeply human. Ebony wasn’t a character. Ebony was a message.

Their spiraling descent wasn’t collapse. It wasn’t weakness or age or decline. It was surrender. It was a deliberate returning to earth, to origin, to root.

And their rising wasn’t effort. It wasn’t strain. It wasn’t defiance of gravity. It was emergence. It was a lifting from truth. It was that ancient pattern of down-into-shadow and up-into-light. It was the true rhythm of transformation. It was also the rhythm of aging, if we let it be: not diminishing, but distillation into essence.

As Ebony’s form shifted, the nose sharpened, the cheekbones rose, the eyes deepened. They took on the geometry of a bird. Not literally, but symbolically. Birds see from above. They traverse realms. They carry messages. They balance effortlessly. Ebony became less human and more like an elder spirit, a watcher, a presence that stands at the crossroads between the earthly and the ascendant. Their final perch-like stance didn’t simply look like balance; it looked like perspective.

I wasn’t alone in that dream. I was part of a crowd. Their faces meant nothing, but their presence meant everything. I wasn’t receiving a private telegram. I was witnessing a universal message delivered in a room full of humanity, even if I couldn’t name a single person in it.

What surprised me most wasn’t the transformation. It was the love. I didn’t admire Ebony. I loved them. And that love wasn’t directed outward. It was recognition. I wasn’t watching someone else become extraordinary. I was watching a truth within myself step into view.

And perhaps most striking of all was their certainty. Every motion—the descent, the ascent, the impossible somersault—unfolded with the calm conviction of a being fulfilling its purpose. They weren’t performing. They were revealing. They didn’t try to succeed. They embodied success. Watching Ebony was like watching destiny moving through muscle and bone.

I’ve lived long enough to know that dreams like this don’t arrive to flatter us. They arrive to remind us. To unearth something we’ve forgotten. To widen the frame. To flip the narrative about aging, limitation, and impossibility.

Ebony didn’t come to tell me I’m special. Ebony came to tell me I’m not alone.

Because what unfolded in that charcoal dream happens in quieter ways in every life. We all descend. We all rise. We all tighten into a truer shape than the one we started with. The story of our lives is a long spiral into becoming.

What Ebony modeled with every fluid turn was the power of moving in alignment with our deepest truth, with the certainty of someone fulfilling their purpose. Not arrogance. Not bravado. But a quiet internal knowing:

This is who I am.

This is what I’m here for.

This is the shape my becoming must take.

Ebony wasn’t hoping to land the somersault. They had already landed it in intention before the body ever followed.

And that, I believe, is the invitation for all of us:

To move toward the life that feels destined.

To step into the self that feels true.

To let doubt loosen and purpose clarify.

To embrace the possibility that becoming doesn’t stop—not with age, not with loss, not with time.

Life doesn’t narrow as we grow older. It deepens.

Sometimes, in the quiet hours before dawn, a presence appears, not to frighten us, but to awaken us. A reminder. A revelation. A truth we’ve grown old enough to finally understand.

I call them Ebony.

They came to show me what’s possible.

They came to show us all.