“Somewhere, an editor is waiting to fall in love with what I’ve written. That’s not ego. That’s faith.”

—Brent L. Kendrick (b. 1947). Blogger, literary scholar, creative nonfiction writer (who loves to fool around in bed), and once-upon-a-time professor who splits his reinvention time between restoring lost voices of American literature and discovering new ways to live, love, laugh, and write with meaning. He’s been sighted in the mountains of Virginia. (Authorial aside to all editors: Sit up and take notice—because if you snooze, you lose. This dude’s relatively cheap, cleans up well, once got compared to Garrison Keillor by someone in Tennessee, and yes—he’ll bake sourdough and seduce the annotations, headnotes, footnotes, and endnotes into (mis)behaving.)

Stats?

Oh. Sorry. I don’t mean my vitals. Though I do check them daily. Why not? My Fitbit provides it all, right on my wrist. Heart rate. Breathing rate. Temp. Heart rate variability. Blood oxygenation. Stress. So, yeah. I check those first thing every morning when I wake up.

I meant another set of stats that matter to me.

My WordPress stats.

I like to know how many people are checking out my blog on any given day.

I like to know what countries they’re from.

I especially like to know what posts they’re reading. That info lets me know what’s hot and what’s not. Every now and then, I lean in and almost let myself believe that what’s hot might just be me. I do. Really. I do. Especially when I see hits on my About Me or About My Blog or Contact Me pages. Like the time one lone reader from Lithuania clicked through twelve posts in an hour—and paused on “About Me.” I remember thinking:

“This is it. This is my moment.”

I guess I figure that if someone is going to all the trouble of background snooping, they’re probably on the verge of being the genius who goes down in history as the one who discovered me, thus ensuring that I go down neither unfootnoted nor unnoted.

Me? Discovered?

Don’t scoff! Stranger things have happened, you know. I mean, I wouldn’t be the first writer catapulted into history and literary fame by an editor with deep belief and keen vision.

One writer who has just been catapulted into history comes to mind immediately.

Alexander Gordon (c. 1692-1754).

Did I just hear you gasp:

“Who’s that?”

Surely, I did not, for if you don’t know who he is, then you must not be the faithful follower I know you to be.

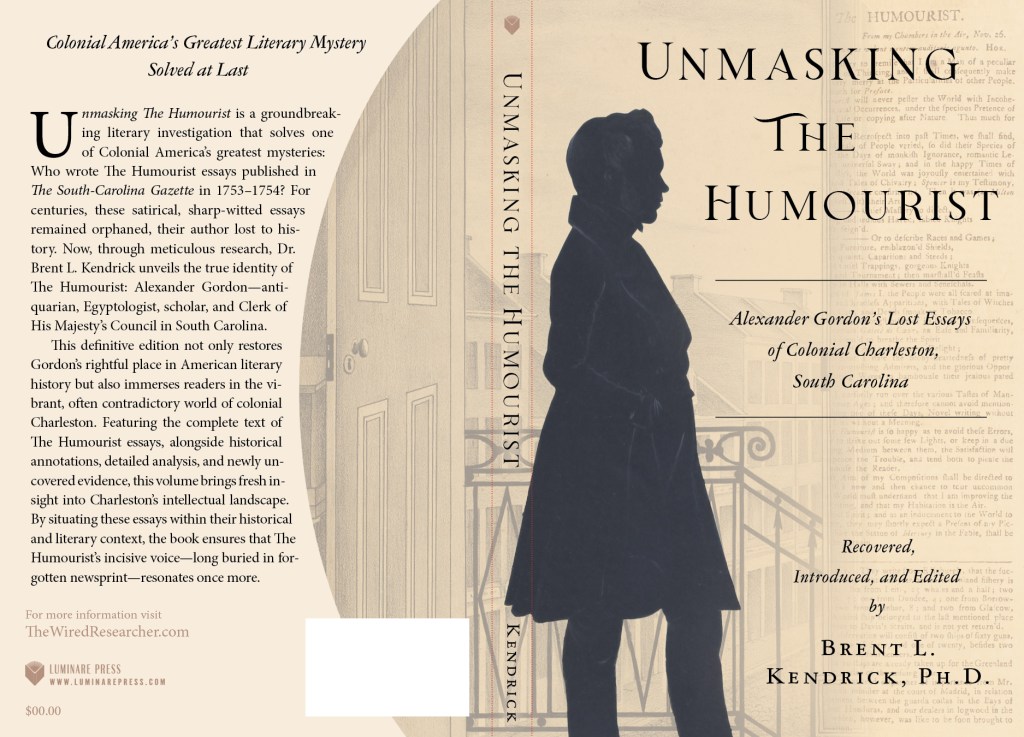

If you’re following me–my blog, I should add for your clarity and my protection–then you know that I recently finished a book about Alexander Gordon, the long-forgotten colonial satirist who published his literary works pseudonymously in The South-Carolina Gazette in 1753-54 under the name The Humourist, and then—like so many voices history forgets—he vanished. No one knew who he was. One scholar asked. But he didn’t bother to find out. No one else did, either. Then I came along. I had a lot of curiosity. I had a tolerance for long hours in dusty archives. Eventually, I had a hunch, and I discovered a clue.

“What happened next?” you ask.

I found him. I pieced together the man behind the pen. I wrote him back into existence. Now, he lives once more for all the world—including you—to read and enjoy again. Unmasking The Humourist: Alexander Gordon’s Lost Essays of Colonial Charleston.

So don’t tell me that a writer getting discovered is a myth. I just did that very thing with Alexander Gordon. Guess what else? It occurs to me that he now stands as the first American writer to be thrust by an editor into fame.

Yes. That’s true and, I’ll make that claim. Right here. Right now.

Someone just upbraided me:

“Excuse me. You’re wrong. Anne Bradstreet was the first.”

Being upbraided is something up with which I will not put.

“So ekscuuuuuuuuuuse meeeeee! You’re wrong.”

Here’s why.

I know. I know. You’re probably thinking about her one and only book The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung Up in America. In case you don’t know the story surrounding its 1650 publication, it goes like this. Her brother-in-law John Woodbridge spirited her manuscript off to England and published it behind her back, unbeknownst to her.

Bradstreet herself seems to back up that claim, especially in her “The Author to Her Book” offering up her well-known and oft-quoted lament:

Thou ill-form’d offspring of my feeble brain,

Who after birth didst by my side remain,

Till snatched from thence by friends, less wise than true,

Who thee abroad, expos’d to publick view,

Made thee in raggs, halting to th’ press to trudge,

Where errors were not lessened (all may judg).

How convenient for Bradstreet. Her posturing created a persona of Puritan modesty and aversion to recognition as compelling as the narrative of her “stolen” book of poetry—the very tale that helped catapult her into public view.

But here’s the thing. Actually, two things. First, Woodbridge was not her editor. Second, despite the storybook notion that Bradstreet considered her womanly role subordinate to the role of Puritan men, scholars maintain that it was “a propaganda campaign” launched by Bradstreet and her family. I’m thinking particularly of Charlotte Gordon’s “Humble Assertions: The True Story of Anne Bradstreet’s Publication of The Tenth Muse,” maintaining that Bradstreet was not surprised by the publication of her book and that, in fact, she was actively involved in its publication.

So there! Bradstreet does not beat Alexander Gordon when it comes to the first American writer thrust into fame by an editor.

But let me not digress from the claim that I am making. Think as long and as hard as you will about American writers between the publication of The Tenth Muse and the publication of the Humourist essays, and if you can come up with someone else who can seize the claim, reach out to me, and I’ll blog it. Better still, reach out to me, and we’ll co-blog it.

But I won’t hold my breath. The Humourist remained pseudonymous from his first November 26, 1753, essay through his final notice on April 9, 1754, known but to God. That is until I came along and solved the greatest literary mystery in perhaps all of American literature. I unmasked The Humourist and revealed him to be none other than Alexander Gordon, clerk of His Majesty’s Council in South Carolina.

Now, through my dogged determination, my literary sleuthing, and my scholarly editing, Gordon will be known forever more and throughout the world as the acclaimed author of the Humourist essays, among the liveliest and most original voices in Colonial American Literature, right up there and on par with Ben Franklin’s Silence Dogood essays.

Needless to say, there have been other American writers who were brought into public view by editors–all boasting just a smidgen of modesty, of course, comparable to mine–who knew talent when they saw it.

I’m thinking of my lady Mary E. Wilkins Freeman and my book The Infant Sphinx: Collected Letters of Mary E. Wilkins Freeman. Although I edited the letters, provided thorough annotations, and wrote biographical introductions to the book itself and each of its five sections, I’m not the editor who discovered her on her way to literary stardom.

Credit for that goes to someone else. Here’s the brief backstory. Freeman started her career as a children’s writer but then extended her literary efforts into the realm of adult short stories. Lippincott’s, Century, and the Atlantic rejected her “Two Old Lovers.” Then she sent it to Mary Louise Booth, editor of Harper’s Bazar, who read the story three different times during three different moods, as was her custom, and accepted it for publication in the March 31, 1883, issue. From that point forward, Freeman wrote regularly for the Harper’s Bazar and Harper’s Monthly, and, in fact, Harper & Brothers became her regular publisher.

In a way, then, it was Mary Louise Booth’s editorial acumen that escorted Freeman into the international literary acclaim she continues to enjoy even today, though in fairness to Freeman, her talent was such that it would have found its way into the spotlight in one way or another. Talent will always out.

I could go on and on with this litany of writers who were discovered by editors, sometimes against the odds. I’m tempted to say that I won’t, but on second thought, I think that I will share with you snippets of some paired writers and editors who come to mind.

I’ll start with Flannery O’Connor, so well known for her bold and unconventional Southern Gothic voice. It was Robert Giroux, an editor at Harcourt who believed in her debut novel, Wise Blood, and guided it into print—despite its eccentric style and religious overtones.

Or what about Jack Kerouac? His On the Road was originally a 120-foot scroll—raw, unfiltered, and “unpublishable.” But Viking Press editor Malcolm Cowley saw gold and helped shape it into the beat-generation classic it became.

Then we’ve got a postal worker with a cult following in underground poetry circles: Charles Bukowski. He caught the attention of John Martin at Black Sparrow Press. Martin offered him a year’s salary to quit his job and write full time. It was the start of a prolific and gritty career.

No doubt you know the minimalist voice of Raymond Carver. His works might have stayed buried had it not been for Gordon Lish at Esquire. Lish gave Carver his break, though not without some brutal edits.

Closer to me and my situation in many ways is Frank McCourt, who, as a retired teacher in his 60s, wrote Angela’s Ashes. Nan Graham at Scribner wept when she read it and championed it into publication. Oh. My. It won the Pulitzer. It sold millions. My kingdom for a Nan.

And if McCourt was close to me occupationally—educator turned writer; I, of course, am still living according to most recent news reports—then I have to mention Jeanette Walls, whose roots are close to mine since we’re both West Virginians. Her memoir The Glass Castle was going nowhere fast until editor Deb Futter read it and saw its power. Her support turned it into a bestseller and reshaped what memoir could be.

And last but perhaps most important to the hope that I carry (like a well-worn talisman) that an editor will discover me and, in a poof, turn me into star dust is Andy Weir. He self-published his The Martian chapter by chapter online. Julian Pavia at Crown Publishing read it, loved it, and bought it. The novel became a bestseller and hit film.

Oh. My. God. I’m doing exactly what Weir did. I’m publishing all of my Foolin’ Around in Bed essays right here, week by week. Once again, my kingdom for a Pavia unless a Nan has already catapulted my bed into fame.

I could share other snippets, but I confess. Right now, I’m in a pickle. But don’t worry. I have a way out. It will work for me, and, as you are about to see, it will work for you too.

I’m going to do what Margaret Atwood did in her story “Happy Endings.” I’m going to give you options.

A. What happens next? Don’t be so impatient. History is based on facts and evidence. Come back for the ending when the ending is written.

B. What happens next? Dear Reader, you know exactly what comes next. Yours truly–Brent(ford) L(ee) Kendrick–aka TheWiredResearcher—keeps right on doing what he’s been doing with his writing and his research. And he keeps right on hoping that an editor–a believer—is out there, poised and ready to do for him what he’s just done for Alexander Gordon.

Not just this blog. Not just my Foolin’ Around in Bed essays. But Gordon. Freeman. Years of words, research, story, and sweat. A whole body of work—waiting for the right editor/reader to say: “This one. This voice.”

“Which ending do you like?” someone queried.

I much prefer B. After all, keepin’ on keepin’ on is the road I’m traveling. Even if it is the one less traveled by, it makes all the difference. Especially when it leads past the stats and toward the stars. (Whew! What a relief. I figured out a way to bring Robert Frost into this post. It’s been too long–far too long.)

Besides, putting aside my own preference for an ending, I have no doubt in the world that right now, an editor is out there who believes in me, who might be scrolling through my “About Me,” pausing over a sentence, clicking “Contact Me,” and thinking:

“This one. This voice.”

OMG. I just felt the earth shift.

I did. I really did.

Did you?

No? You didn’t?

Don’t worry. Be happy. Somewhere, right now, someone’s opening a drawer, clicking a link, or flipping a page—and everything’s about to begin.

It’s just a matter of time and a matter of stats.