“Give a man a mask and he will tell you the truth.”

—Oscar Wilde (1854–1900), Irish playwright, novelist, critic, and a master of wit, paradox, and social satire.

Humor means different things to different people.

Sometimes it appears when something almost goes wrong but doesn’t. The tension releases, and everyone exhales at once.

Sometimes the biggest laughs come when someone names a behavior we all recognize but rarely admit—family habits, social pretenses, small vanities we pretend not to see in ourselves.

Humor lets people say risky things safely. We soften criticism with a joke. We test opinions indirectly. We disagree without declaring war.

Sometimes humor does something even simpler: it lets strangers feel briefly aligned. People who laugh together feel, if only for a moment, that they belong to the same world.

I can relate to all of those kinds of humor.

But lately I’ve been tapping into another kind of humor. Laughing at myself.

Because here I am, at this stage of life, carrying the bags of a Colonial American writer who performed behind his own joke for nearly 275 years.

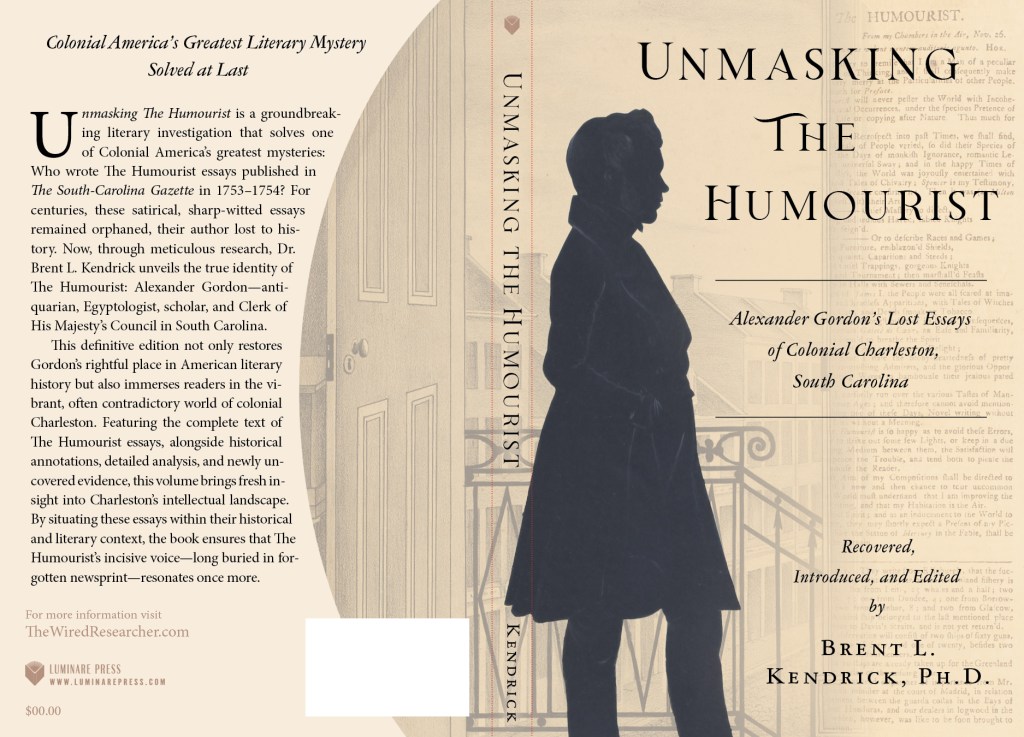

He wrote in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1753 and 1754 under the pseudonym The Humourist. I eventually identified him as Alexander Gordon—antiquarian, playwright, former operatic tenor, Egyptologist, and Clerk of His Majesty’s Council—and published the essays in my book Unmasking The Humourist: Alexander Gordon’s Lost Essays of Colonial Charleston, South Carolina.

Right now, I’m laughing out loud as I finish typing that last paragraph. It captured all the necessary details in so short a fashion that a reader who doesn’t know about my work might think it was easy.

It wasn’t and that’s no laughing matter.

I started working on these pseudonymous essays in 1973, and it took me decades of on-again-off-again research to solve what was the greatest mystery in all of American literature. Who wrote the essays that were right up there with Benjamin Franklin’s?

I solved the mystery by giving the essays a close reading and by developing a precise profile of the pseudonymous author.

He shows deep classical learning; fluency in music and theater; detailed knowledge of colonial legislative procedure; access to the printing process; and—most strikingly—specialized antiquarian expertise, including repeated, highly technical references to Egyptian mummies.

That last detail matters—hold on to it.

Serendipity helped. While combing the South Carolina Gazette for anything that might name the author outright, I stumbled on an obituary for Alexander Gordon, Clerk of His Majesty’s Council. The obituary didn’t identify him as The Humourist, but as I dug further, Gordon’s life and learning aligned almost point for point with the profile my close reading had built—especially the mummy trail.

Egyptology was not casual learning in colonial Charleston. Yet the essays speak in depth about mummies, and Gordon’s will independently inventories Egyptian paintings and drawings and an unpublished manuscript on Egyptian history. When the essays and the archival record illuminate one another so precisely, alternative candidates disappear. The mask does not merely fit. It belongs—and suddenly the performance comes into focus.

With Gordon restored to authorship, the essays change. They stop being a curiosity and become something far more interesting: a sustained experiment in humor and performance inside the colonial newspaper itself.

Attribution reveals design. What once appeared as scattered satire resolves into a deliberate experiment—using humor, performance, and print itself to create a conversation between writer and public.

Recently, I explored that angle for a talk at the South Central Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies in a paper titled “Pleasure, Play, and the Colonial Press: Unmasking The Humourist in Eighteenth-Century Charleston” — I realized something unexpected.

The real story is no longer the mystery.

Now that the mystery has been solved, the authorship established, and the essays restored to print in Unmasking The Humourist: Alexander Gordon’s Lost Essays of Colonial Charleston, South Carolina (2025), readers can finally approach them not as an attribution puzzle but as a serious contribution to colonial American literature — and to eighteenth-century humor itself.

What emerges is humor doing real cultural labor.

Gordon deploys mock-serious moralizing, feigned modesty, fabricated correspondence, and theatrical self-presentation to probe colonial life. He stages debates with himself, parodies authority, and moves constantly between sincerity and self-mockery. Humor here is not decoration or diversion. It becomes a way of negotiating civility, reputation, and power in a city both ambitious and anxious.

Just as important, the humor is local. Charleston is not London or Boston. Gordon writes within a transatlantic essay tradition, yet his satire is tuned to a specific press, a specific readership, and the particular pressures of a provincial colonial capital learning how to see itself.

One of his most sophisticated devices is fabricated correspondence. Figures such as Alice Wish-For’t, Urbanicus, Calx Pot-Ash, and Peter Hemp enter the newspaper as letter writers, each occupying a recognizable social position. Alice Wish-For’t blends patriotic seriousness with playful irony, turning courtship into commerce as she urges Carolina to favor its own “manufactures.” Urbanicus performs civic refinement, respectfully cataloguing Charleston’s dangers until earnest reform quietly becomes satire. Calx Pot-Ash and Peter Hemp speak as commodities seeking settlement, reducing questions of empire and policy to negotiations among trade goods.

Equally telling is where these voices write from — England, Sweden, Russia. Distance lends authority while keeping Charleston firmly at the center. The newspaper becomes a stage upon which local life is judged through transatlantic eyes.

Of course, Gordon writes all the letters himself.

Yet the illusion matters. Humor manufactures sociability, creating the sense of an engaged public responding in real time. The newspaper becomes not a lecture but a space of play, populated by voices entering and exiting as if directed from behind the curtain.

That play extends even further — to authorship itself. Rather than locating comedy only in scenes of leisure, Gordon repeatedly turns writing into the joke. The Humourist exists entirely in print, negotiating with readers, printers, and critics while never stepping outside the role he has invented. Apologies, promises of reform, threats of retirement, and editorial decisions mimic literary authority even as they quietly undermine it. Print culture itself becomes performance.

At moments he turns this playfulness toward authority directly. In a mock proclamation issued by Apollo, styled “King, Ruler, and sole Arbiter of Parnassus,” poetry is regulated like civil law, offending writers condemned in language borrowed from official decrees. The humor lies not simply in exaggeration but in recognition: authority, literary and political alike, depends on performance.

By this point, the pattern becomes unmistakable. The newspaper has become a stage. Voices circulate, authority performs itself, and meaning moves through print while a hidden author directs the scene.

The experiment reaches its height in the Humourist’s carefully managed disappearance. His farewell dramatizes authorship itself, insisting he will never again “enter the Lists of Authorism.” Timing, posture, and voice — the very tools of authority — become part of the joke he appears to control.

Here humor shifts away from events and toward the performance of authorship itself, as the writer gradually becomes part of the joke he has created.

Once we recognize that experiment, we can finally ask a larger question:

“What, exactly, did my scholarly research really recover?”

Not just an author’s name. Not just a solved literary mystery.

What returns is pleasure—yhe pleasure of wit, play, and performance in the colonial press.

These essays can now be read, taught, and argued over not as anonymous artifacts, but as the work of a specific and remarkably complex mind. They invite us to reconsider early American literature not as solemn beginnings, but as lively experimentation — writers testing ideas about society, behavior, and power through laughter.

I keep carrying Gordon’s bags.

From Charleston, where he wrote them. To Deltaville. To Pinehurst. And wherever the conversation goes next.

Because if humor helped him speak safely to his own century, perhaps it can help us hear him clearly in ours and remind us that one of the sharpest, funniest voices in Colonial American literature was never lost.

He was simply waiting for the joke to land.

So I keep carrying the bags—following the voice that once spoke from behind the mask, wherever the road leads.

.